One of the most important scientists of the western tradition, and about whom we in America know little, is Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), a Prussian polymath who amazed contemporaries like Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Charles Darwin, and Simon Bolívar, the South American liberator. Our ignorance persists despite the hundreds of appearances of his name, around the world: the Humboldt Current, the Humboldt penguin, Mare Humboldt on the moon, Humboldt County in California, Nevada and Iowa, Humboldt University in California, Parque Nacional Alejandro de Humboldt in Cuba, Alexander von Humboldt National Forest, Peru.

Andrea Wulf, author of five books of science and history, sets out to help us see and appreciate the man and his work in The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World (2015)

Andrea Wulf, author of five books of science and history, sets out to help us see and appreciate the man and his work in The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World (2015)

The first half of the book introduces the man, the amazing reach of his mind, his indefatigable energy, his voluble presence among family and peers. For five years he trekked in South America, often with only a companion or two, no supply chains or hi-tech outdoor gear. He showed that the mighty Orinoco of Venezuela and the even more mighty Amazon were connected by a natural canal called the Casiquiare. His almost complete ascent of 20,702 foot high Chimborazo to a height of 19,286 feet, without ropes or boots, but plenty of altitude sickness, remained a mountain-climbing record for nearly 30 years.

As he followed the Amazon or crossed the Andes he did not just look and wonder and jot down impressions. He kept detailed records of minutia, measured and catalogued, and of the grand order of nature as it was beginning to compose itself in his mind.

“I shall try to find out how the forces of nature interact upon one another and how geography influences plant and animal life. In other words, I must learn about the unity of nature.”

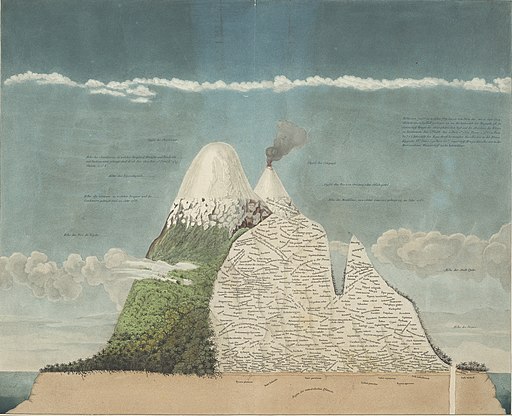

Not content to assemble data in tables and charts, he created colorful representations of what he had found, as here in a representation of Mt Chimborazo in present day Ecuador, with plants and other features at proper elevations. The full map has more detail in columns at the left and right margins.

Surface features were not enough. In another incredible piece of work he opens up earth’s interior as he then knew it

Ω

The second half of the book looks at the wide, powerful influence Humboldt had, through his writings and the force of his personality, on his peers, and through them on all of us, from Thomas Jefferson and Charles Darwin to Henry David Thoreau and John Muir.

By the time of Darwin’s voyage on the Beagle in 1831, Humboldt had published his Personal narrative of travels to the equinoctial regions of America, during the years 1799-1804 / which Darwin wrote that “… it had stirred up in me a burning zeal.” In the spring of 1831 before he was offered the position on the Beagle he “read and re-read” Humboldt. In fact he carried it with him on his own five-year voyage.

“I spent a very pleasant afternoon lying on the sofa, either talking to the Captain or reading Humboldt’s glowing accounts of tropical scenery. — Nothing could be better adapted for cheering the heart of a sea-sick man.” (Dec 31)

By the time John Muir was exploring Yosemite Valley in 1868, Humboldt’s five-volume Kosmos (1845 — 1862 ) in various English translations had been out for more than twenty years. Humboldt himself was a major celebrity in America as well as in Europe. On the anniversary of his birth September 15, 1869 headlines across the U.S. announced marches, gatherings, public honors and speeches commemorating him. Muir read him constantly and through own his writing and advocacy helped turned Humboldt’s foundational work into the modern environmental movement.

It is hard to overstate Humboldt’s influence – in his foresight of wanting data to determine the effect which the destruction of forests had on climate; in his innovative use of data and graphics in combination; oin his insistence that science and sensual appreciation of nature were both vital. He initiated a world-wide network of geomagnetic observation stations which collected over two million data points in three years. His books and papers, written for both scientists and the reading public, were instrumental in laying the foundations of current day environmental knowledge.

Besides naturalists and scientists such as Darwin and Muir, two others, whose fame and contributions have also been eclipsed, yet who were instrumental in the advancement of science and especially biology were George Perkins Marsh, an American and Ernst Haeckel, a German.

Marsh’s 1864 Man and Nature was one of the first scientifically based warnings of the destruction of nature by man. The first paragraph of the Preface read:

The object of the present volume is: to indicate the character and, approximately, the extent of the changes produced by human action in the physical conditions of the globe we inhabit; to point out the dangers of imprudence and the necessity of caution in all operations which, on a large scale, interfere with the spontaneous arrangements of the organic or the inorganic world; to suggest the possibility and the importance of the restoration of disturbed harmonies and the material improvement of waste and exhausted regions …

(Who knew that the conspiracy of tens of thousands of scientists, world-wide, warning us of global climate change, began 155 years ago, in the midst of a great civil war?!)

Ernst Haeckel was a zoologist and artist, whose brilliant drawings of radiolaria, and other small sea forms were revelations. He too, looked to Humboldt as his predecessor and inspiration.

Virtuosity in observation of nature and in integrating the many in the one was not the only thing that singled Humboldt out. Dying just before the U.S. Civil War, he lived his adult life during the fullest development of European slavery and contempt for non-white peoples around the world, Somehow he escaped this cultural prison. He abhorred slavery and serfdom and said so, repeatedly. He was unstinting in his condemnation of colonial rule and in favor of emancipation. Almost uniquely among, even anti-slavery people, he held that negro and indigenous people were as fully human and capable as their tormentors.

As early as 1800, three years before he met the slave-holding President Thomas Jefferson, he traveled in Spanish slave-holding Cuba, writing,

Slavery is, without doubt, the greatest of all the evils ever to have befallen mankind, whether one considers the slave who is torn away from his family in his place of origin and thrown into the hold of a ship converted into a slave-trading vessel or whether he is seen as part of a hoard of black people who are herded together on the soils of the Antilles; nevertheless, the degree of suffering and deprivation endured also varies in individual cases.

On Humboldt’s death, in 1859, a writer to the New York Times reported a conversation with him in 1853 in which he had said,

“The experiment of freedom and slavery side by side … will end in failure. The two cannot co-exist in the same government. They are as antagonistic as oil and water. A gigantic war will be the certain result, and I do not think war can be postponed longer than eight years.”

He was denied a visa to visit Russia for several years for fear he would call attention to the condition of the people he would inevitably encounter. In 1829 at the age of sixty he was finally given the opportunity to visit Russia and Siberia.The government of course wanted his mining-engineer opinion of newly developed gold and platinum mines in the Urals. As a condition of travel Humboldt had to promise to refrain from commenting on the political situation and condition of the serfs of the country.

His friendship with Simón Bolívar, and shared love for the South American continent, provided Bolivar inspiration in his long fight for freedom agaisnt the Spanish, and to designate wide swaths of the liberated land as national treasures, not to be destroyed for mining and cattle. His long essay, The Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain, was influential in shaping attitudes towards the end of colonial power.

Ω

The problem of having one’s eyes opened is of course that we realize they could be opened even more. Several of Humboldt’s works are available at Gutenberg, especially the three volumes of Personal Narrative which so influenced Darwin. The first volume of Cosmos, the hugely influential five volume series is also available. For a brief shout-out to Cosmos see here. George Perkins Marsh’s Man and Nature is also available, as is much of Ernest Haeckel’s work. Thoreau bears a re-reading, with Humboldt in mind as does John Muir, who although a modern saint in the Church of Earth, most of us have read little.

Great recap of Wulfs overview of Humboldt’s life and many contributions to the natural sciences and human rights. He was the father of ecology in helping us see and understand the relationship s among species at a time when explorers focused on species one by one. And many other dynamics involved in natural systems.